Township of Muker; multiple place-names within an area about a mile and a half around OS grid reference SD9199 – a farmstead or former territory, a gorge, a waterfall, a distinctive isolated hill, parts of some high moors, and other, lesser-known, high-altitude features.

The origin of the name Kisdon is obscure and puzzling for many reasons. The downloadable pdf below contains a 7,000-word article setting out the possibilities for its original meaning and suggests that the most promising is ‘gravel valley’, a name for the distinctive section of the valley of the River Swale as it descends southwards from Kisdon Force to the river’s confluence with Straw Beck; and a name now lost to the valley but surviving attached to several surrounding landscape features.

Scroll past the pdf download to continue reading this much shorter and more-digestible summary of the discussion and the findings.

Summary of the discussion and findings

The most immediately intriguing aspect of Kisdon is the large number of topographical features that are identified by the name and that are clustered around this stretch of the valley of the River Swale. The three best-known Kisdon place-names are highlighted on an old Bartholomew map (above). They are a waterfall on the River Swale, called Kisdon Force, an adjacent large and distinctively isolated hill, called Kisdon or sometimes Kisdon Island, and a farmstead on the hill’s south-east flank, called Kisdon or Kisdon Farm. The steep sides of the dale around Kisdon Force have given rise to its locally recognised name of Kisdon Gorge, although this is probably a modern creation because there are no historic records of it. It’s clear that the name Kisdon has been borrowed over time from one feature to another. The most recent borrowings are probably those of the gorge and waterfall, taking their names from the adjacent, large, isolated hill. But was the isolated hill the original Kisdon, as many might assume, or was the name borrowed from something else nearby?

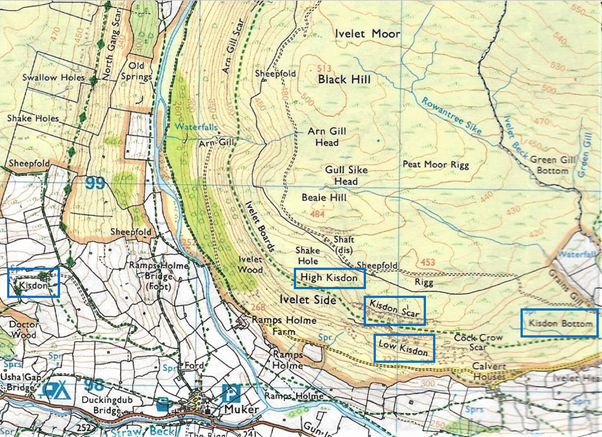

A possible route to answering the question is to understand the nature of the several Kisdon place-names and to try to analyse the relationships between them. Opposite the farmstead, on the other side of the River Swale, adjacent to where the river turns sharply eastwards, and high on the corner of what becomes the south-facing daleside, there are another four Kisdon place-names – High Kisdon, Low Kisdon, Kisdon Scar, and Kisdon Bottom – all labelled on the current OS Explorer Map (below). Earlier six-inch OS maps also show Kisdon Well, a springhead at Kisdon Bottom. In addition, there is a locally known name – Kisdon Folds, a sheepfold at High Kisdon.[1]

Seen here highlighted on the current OS Explorer Map, OL30 Yorkshire Dales Northern and Central Area, are Kisdon farmstead (at left) and, on the opposite side of the dale, four other Kisdon place-names. Image Microsoft Bing. Map © Ordnance Survey.

In The Place-names of the North Riding of Yorkshire (English Place-name Society vol. 5, 1928), the eminent place-name scholar A H Smith (1903-67) expressed opinions on several upper-Swaledale place-names, but not on Kisdon. He was probably deterred by the lack of recorded early spellings, which are invariably required to make any confident assessment of the original meaning of a place-name. No other place-name expert has formally investigated the name, so this article is an amateur’s attempt to solve the puzzle.

I have had some professional help. I am grateful to Diana Whaley, Professor Emeritus of Early Medieval Studies at Newcastle University, and a past president of the Society for Name Studies in Britain and Ireland, for generously commenting on and developing an earlier investigation of mine into this cluster of Kisdon place-names, and for giving me some very useful pointers, including identifying some early records of the name that I had not found. I am also grateful for ideas and encouragement from my friend Richard Walls, of The Old School Art Gallery and Craft Centre at Muker, who is a photographer, author of Kisdon Landscapes, and fellow amateur place-name sleuth.

The earliest known record of Kisdon, is found in the Cartulary of Rievaulx Abbey, dated 1538, on a list of lands owned by the monastery at the time of its dissolution. It referred, not to the now well-known hill, but to the agricultural landholding of that name, at which rents were collected from three tenant farmers, William Metcalfe, Edmund Milner, and Ralph Milner. The spelling in that record is Keisden.[2] Two other records from the same period, also referring to the landholding, named it as Keisdon, with a different ending of -on (1539/40) [3] and as Keysdom (1544).[4] All three spellings have been sourced from transcriptions of manuscripts and so might contain transcription errors. The -m ending, whether it is in the manuscript or only in the transcription, can almost certainly be taken as intended to be -n. Spellings in more-recent records have all been found in original manuscripts, microfilm copies of which I have seen and digitally copied. Most are references to the productive agricultural landholding. Others, where noted next in brackets, are manuscript map labels referring to the isolated hill. The spellings in chronological order are: 1669 Kisdon,[5] 1715 Kysdon,[6] 1760 Kisden,[7] 1761 Kisdon (the hill),[8] 1762 Kisdon,[9] 1771 Keasdon Island (the hill),[10] 1780 Kisdon,[11] 1787 Keasdon Isle (the hill),[12] 1818 Kisdon,[13] 1829 Kisdon.[14]

The names of the places we now call Kisdon could have been coined at any time from the seventh century, when the early-Old-English (OE)-speaking Angles progressed from central Yorkshire to the north-west of England, or from the tenth century when Old-Norse (ON)-speaking Norwegian Vikings migrated from an earlier settlement in Ireland, or later from any of the early centuries after the Norman Conquest, when the general population of Yorkshire is considered to have been largely people of blended Anglo-Scandinavian descent. Unfortunately, even the earliest 1538 record of the spelling we have, is not early enough to allow a confident linguistic analysis, either of the period in which it was first coined, or of its original meaning. By 1538, the language had evolved from Old English (OE, roughly 450-1150), through the period of Middle English (ME, roughly 1150-1500) and arrived at the early stages of the development of Modern English (Mod. E). The only consolation is that the 1538 spelling was at least recorded by a monastery scribe and so could be considered one of the most reliably accurate records of that time.

Despite the lack of Old-English or Middle-English spellings, there is merit in trying to analyse the elements of the name in 1538 to see what clues they might offer to the original meaning. Then, given that a large proportion of early English place-names comprise words for the type of landscape of the area,[15] it might be possible to see whether these element words in any way match the actual landscape around this part of Swaledale. That earliest spelling has two elements Keis- and –den. There are many possible explanations for both. All are explored in the fuller article in the pdf. Here are the most promising ones:

Second element – OE –denu ‘valley’ – This is a very common origin of second elements in English place-names, the final -u always being lost. Sometimes the spelling -den remains unchanged but it also frequently evolves into -don or -ton. If OE –denuwas the original second element of Keisden, it must have referred to an identifiably special part of the valley of the River Swale. In fact, the two-mile section of the valley from Kisdon Force in the north, running southwards downstream as far as the river’s confluence with Straw Beck, is very different from the shape of Swaledale immediately upstream and downstream from it. It is special. It runs between the isolated hill now called Kisdon on the west, and which has Kisdon Farm on its south-east flank and, on the opposite, eastern side, the other high-altitude Kisdon place-names. It might be considered a valley distinctive enough to have once had its own name, which was later copied to the farmstead and to the heights on either side of it, even though no locally specific valley name survives today.

A key aspect of OE is the broad range of words describing very specific different types of landscape. Experts have identified the characteristics of a denu-type of valley, and this section of the valley of the River Swale seems to fit them perfectly.[16] A denu is typically long (in this case more than two miles), curving, narrow with steep sides (all evident), and descending by a gentle gradient (in this case falling only about 50 metres, at a rate of about 1 metre in 70).

The notion that this might have been Keis-denu is perhaps undermined by the fact that most of the surviving Kisdon place-names on the east are located beyond the extent of the distinctive denu-type section of the valley. They sit above the River Swale just after it turns sharply eastwards and are best-described as being on the south-facing dale-side. However, it might also be considered that those south-facing places have names copied from the neighbouring High Kisdon moorland, which is just about above the turn of the river and more-or-less opposite Kisdon farmstead.

Another possible objection is that the ending -den, when considered to originate in denu, is rarely found in the northern-most Yorkshire Dales, almost certainly because of the later influence of ON speakers whose own words for landscape features came to proliferate in the area. A H Smith identified only two surviving instances of denu in Wensleydale and one in upper Swaledale, at Cogden, near Grinton. However, potential rarity should not rule it out. It could mean that this is a newly identified survivor of a high-Pennine OE place-name that was coined before the 10th-century arrival of Viking settlers.

First element – OE *cisse/*cis/cisel/*cisen ‘gravel’ [17] – an asterisk indicates words that linguists have deduced from other variants of the word although no direct record of it in this precise form exists. From this group, only cisel is attested.

During the period of ME (c.1150-1500), the French word gravele/gravelle was imported into English and became the norm.[18] The English word survived in some dialects, at least until the 19th century. The adjective chiselly, for a type of stoney soil or for hard bits of wheat in flour or bread, was recorded in several regions, including in North Yorkshire.[19] And the k- spelling, assumed to have evolved through Scandinavian influence, survived as an obscure Scottish term kistle-stone, also written keisyl-stone, meaning flint-stone.[20] It is also significant that what must have been an ancient root-word for gravel survived on the Continent and evolved in Middle High German (c.1050-c.1350) as kis and survives today in Modern German as keis.[21] In England, the most prevalent evidence of survival of the OE word is found in place-names, where Scandinavian influence can also have changed the initial letter to k.[22]

Professor Diana Whaley’s first response to the question of Kisdon, posed to her by my friend Richard Walls, was to suggest that the first element could be kis- from OE *cis ‘gravel’. This has been an inspiring prompt for me because my initial determination to find an argument against it resulted in me finding nothing but arguments to support it. I am also extremely grateful to my friend Les Knight, a professional geologist, for pointing out that glacial valleys like Swaledale can be sources of gravel and sand. Both are contained in alluvial deposits that settled to the bottom of glacial lakes formed along some major valleys as the ice retreated. When the moraines holding back the lake-water broke, they left behind ghost lakes, appearing now as flat valley-bottoms formed by the alluvial deposits.

The stony/gravelly bed of the River Swale in the flat-bottomed valley between the heights named Kisdon. Photograph courtesy Richard Walls.

Where the surviving river has progressively narrowed and cut deeper into the silt, it leaves behind, on either side, higher terraces containing varying proportions of gravel and sand. The photographs and LiDAR image below show that this has been the case in the section of the valley of the Swale from Kisdon Force southwards down to and beyond the confluence of the River Swale and Straw Beck. Significantly, in lowland stretches of the River Swale, below the town of Richmond, gravel extraction is well-known and continues today. There is even a type of river-gravel marketed as Swale Pebbles. This is endorsed by a detailed geological study of the landscape around Kisdon Hill, in which the authors state: ‘Most of the valley bottoms [around the hill] contain thick deposits of glacial and debris-flow diamictons [mixed particles], glaciofluvial sand and gravel, and coarse-grained river gravels.[23]

A notable terrace cut into glacial sediment by the River Swale in the flat bottom of the valley in between the heights named Kisdon. Photograph: Will Swales.

The distinctive flat-bottomed section of the valley of the River Swale, joined at the south end by Straw Beck and lying between several Kisdon place-names. Screenshot from LiDARFinder https://lidarfinder.com. Map data © Google. LiDAR © Environment Agency copyright and/or database right 2015. All rights reserved.

Experts have identified several English place-names that are most-likely to be derived from OE *cisse/*cis/cisel/*cisen ‘gravel’ or ‘gravelly.’ The best-known are Chishill in Essex, Chisenbury in Wiltshire, Chesham in Buckinghamshire, three in Lancashire, at Chisnall, Chesham, and Cheesden, and one in Northamptonshire, at Kislingbury; the latter being especially interesting here because of its initial Scandinavian letter k. In some cases, it has been noted that the linguistic analysis is supported by local gravelly landscapes.[24]

Conclusion

While the absence of early spellings of Kisdon makes it impossible to be certain of the original meaning, there seems to be a good case for the origin of the first element Kis- being a Scandinavianised form of OE *cis ‘gravel’, and for the whole meaning to be ‘gravel valley’. The name would have easily been copied to the heights on both sides of the valley and to the farm or landholding called Kisdon on the side of the most prominent hill. If correct, it would suggest that the name was coined by Anglian settlers some time from about 650 to the end of the 800s, before the arrival of Viking settlers. Later, the need for a name for this specific section of the valley of the River Swale must have become redundant, and so slid into oblivion, surviving only where it had become attached to those features alongside it.

[1] John Waggett, local farmer, personal communication.

[2] Cartularium Abathiæ de Rievalle, Surtees Society vol. 83 (London, 1889).

[3] List of the Lands of Dissolved Religious Houses, from List of Original Ministers’ Accounts, Part 2, Henry VII and Henry VIII, Public Record Office Lists and Indexes no. 24 (HMSO, 1910), reprinted by Kraus Reprint Corporation, as Lists and Indexes Supplementary Series No. 3, Vol. 4 (New York, 1964).

[4] James Gairdner and R H. Brodie, eds., Letters and Papers of Henry VIII, vol. 19 Part 2, Grants in December 1544, Grant 800, no. 5 (HMSO, 1905), p. 469.

[5] Grant in tenant right, Routh Family Papers, North Yorkshire County Record Office (NYCRO), Z2/20.

[6] ‘Inventory of tools … lead works in Swaledale,’ NYCRO ZLB/5/2.

[7] Lease and bond by Anthony Milner, Routh Family Papers, NYCRO Z2/21-22.

[8] Stint agreement, Routh Family Papers, NYCRO Z2/23.

[9] Declaration of arbitration, Routh Family Papers, NYCRO Z2/33.

[10] Jefferys’ Map of Yorkshire 1771.

[11] Routh Family Papers, NYCRO Z2/24.

[12] John Cary’s 1787 map of North Riding Yorkshire.

[13] Muker enclosure awards, NYCRO WRRD B copied from Durham CRO HH 6/3/4.

[14] Muker enclosure awards, NYCRO WRRD B copied from Durham CRO HH 6/3/7.

[15] Margaret Gelling and Ann Cole, The Landscape of Place-Names (Stamford, 2000), xii-xxiv.

[16] Margaret Gelling and Ann Cole, The Landscape of Place-Names (Stamford, 2000), p. 114.

[17] David Parsons, The Vocabulary of English Place-Names Ceafor – Cock-pit, English Place-Name Society (Nottingham, 2004), *cisse/*cis/cisel/*cisen.

[18] Oxford English Dictionary, gravel.

[19] Joseph Wright, English Dialect Dictionary, vol. 1, A-C (Oxford, 1898).

[20] Joseph Wright, English Dialect Dictionary, vol. 3, H-L (Oxford, 1902).

[21] David Parsons, The Vocabulary of English Place-Names Ceafor – Cock-pit, English Place-Name Society (Nottingham, 2004).

[22] See Kislingbury in J E B Glover, Allen Mawer, and F M Stenton, The Place-Names of Northamptonshire, English Place-Name Society, vol. 10 (Cambridge, 1933), pp. 86-87.

[23] James Rose, ‘Quaternary geology and geomorphology of the area around Kisdon, upper Swaledale – an excursion,’ in Yorkshire Rocks and Landscape: A Field Guide 3rd edn., eds. Colin Scruton and John Powell (Yorkshire Geological Society, 2006).

[24] David Parsons, The Vocabulary of English Place-Names Ceafor – Cock-pit, English Place-Name Society (Nottingham, 2004), *cisse/*cis/cisel/*cisen.